“Visual culture refers to the sum total of the visual objects that surround us and the ways in which those can shape our identities, influence our beliefs, and ultimately compel us to communicate visually.”

Dr. Alexander K. Smith

Historically, visual culture was predominantly shaped by those in power, including rulers, religious institutions, and elites, who controlled public spaces and the creation and dissemination of images in art, architecture, and design. It was orderly and aligned to the dominant social structures of the time (Berger, 1972).

Photography, invented in the 19th century, democratized image-making by enabling wider segments of society to create and own visual representations. Unlike painting, which required skill and resources, photography was more accessible, allowing non-elites to document their lives and perspectives.

Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (first written in 1935) noted that mass reproduction shifted art’s value from exclusivity to accessibility, enabling mass consumption and new political uses.

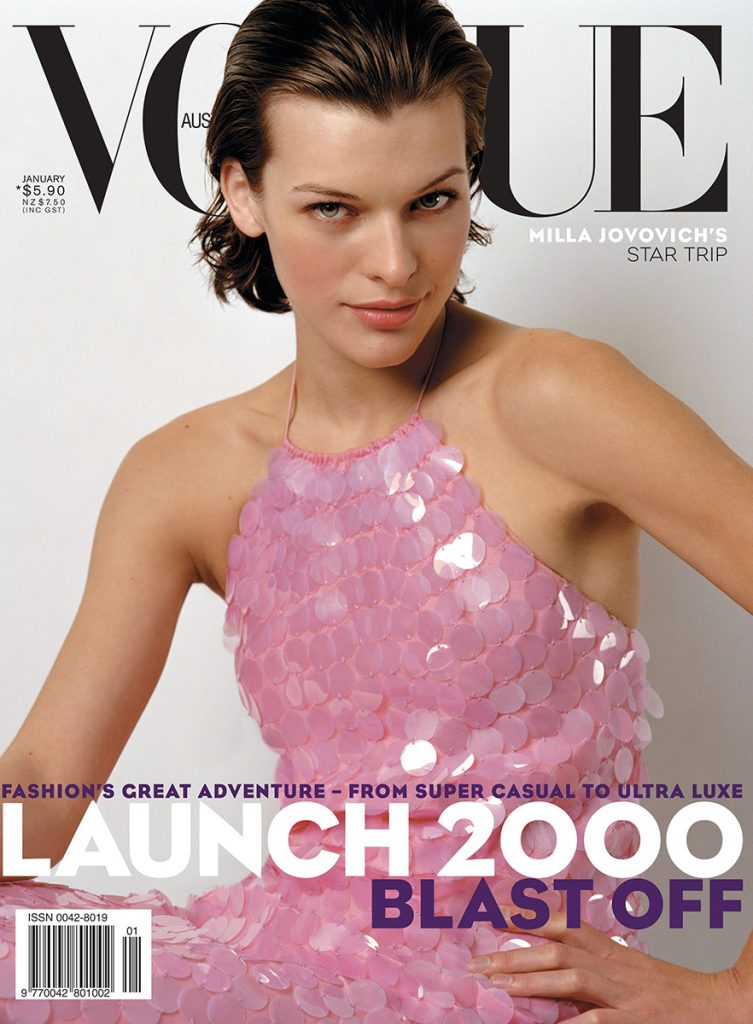

However, even with the help of mechanical reproduction, at the start of the digital revolution, visual culture was still largely controlled and defined by traditional media, which included television, film, print magazines, billboards, and fine art. Public participation was still limited as it was curated by gatekeepers like editors, advertisers, or art institutions.

Visual trends evolved gradually, driven by the industry tastemakers or cultural movements. Creating and distributing visuals required specialized skills, equipment, and access to intermediaries like galleries or publishers.

Our shift to Web 2.0 environment turned this model upside down. Social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube have radically democratized how we perceive the world and engage with it, accelerating the production, consumption, and evolution of visual culture (D’Armenio & Dondero, 2024).

Public space today is social media and is open to everyone 24/7. Global participation is shaping today’s visual culture. It’s playful, feels easy, like a game (Niemelä-Nyrhinen & Seppänen, 2023). With a smartphone, anyone can create, share, and influence visual narratives in real-time. The power to shape visual culture has shifted from traditional gatekeepers (e.g., galleries, elites, media companies) to users. And tools like filters, AR effects, and editing apps, such as Canva or Adobe Express, enable even amateur creators to participate.

Our world is becoming increasingly visual, with visuals replacing text as our main way of sharing meaning, building connections, and making ourselves understood, quickly and across cultures (Adami & Jewitt, 2016; Yang, 2024). 🌎💬👍

Social media platforms create an illusion of intimacy and immediacy, encouraging users to contribute visual content casually and frequently (Zappavigna, 2016). This has made visual culture today a participatory, global practice where aesthetics, identity, and influence are co-created by communities.

Visual culture has become hyper-accelerated. Social media platforms like TikTok enable visuals to go viral globally within hours. This constant churn fuels creativity, but it also creates pressure. Trends disappear as quickly as they arrive, and the pace leaves little room for lasting impact (D’Armenio & Dondero, 2024).

Value is measured through likes, reposts, and view counts, which guide what kinds of images are created and seen.

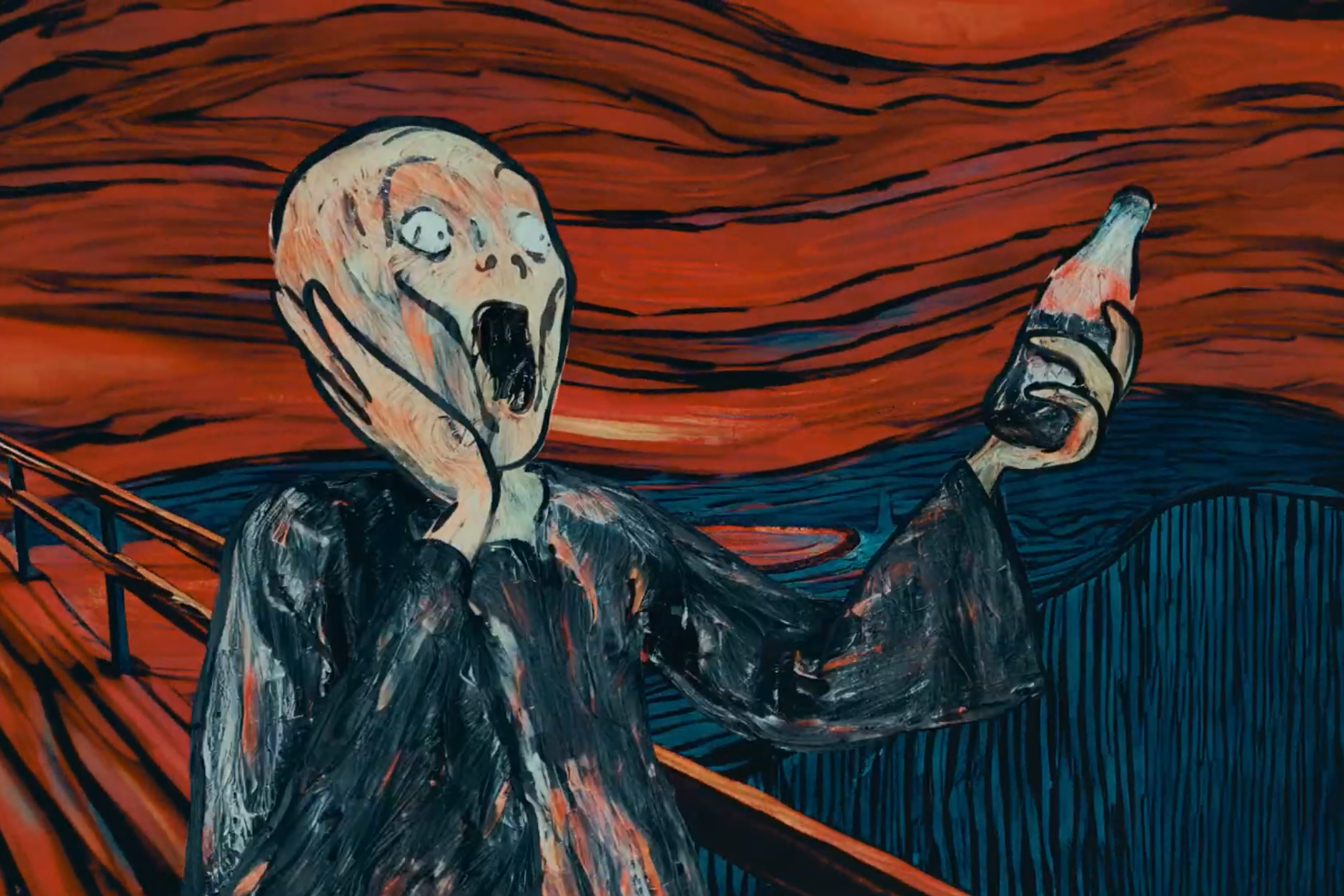

As a result, traditional art movements have been replaced by fast-moving micro trends and platform-driven genres like GIFs, selfies, dance challenges, and memes.

The social media environment also introduced new controls, consisting of algorithms, platform policies, and influencer trends, which influence aesthetics and identities within this interactive environment (Adami & Jewitt, 2016; Zappavigna, 2016).

In the digital age, algorithms have become the tastemakers of the visual design world, quietly shaping the aesthetics that flood our screens. They’ve created a powerful feedback loop. Creators, eager to stand out, appeal to the patterns of what algorithms reward and shape their work to fit their parameters, such as vibrant short-form videos or specific aesthetics, to maximize engagement. As more creators produce content tailored to these parameters, algorithms detect higher engagement and further promote similar content, reinforcing the cycle.

This loop shapes today’s visual landscape and culture, often prioritizing trending styles over diverse or experimental expressions, while continuously evolving based on user input, creating a dynamic interplay between creators, algorithms, and audiences.

References

Adami, E., & Jewitt, C. (2016). Special issue: Social media and

the visual. Visual Communication, 10.1177/1470357216644153

What is visual culture | theory to go 2, & Armchair Academics (Director). (2022, Nov 13).[Video/DVD] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQcJzjxmqqw

Benjamin, W. (1969). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Schocken Books.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. Penguin Books.

D’Armenio, E., & Dondero, M. G. (2024). Introduction: Hyper-visuality: Images in the era of social platforms, digital archives and computational economies. Visual Communication (London, England), 23(3), 405–425. 10.1177/14703572241247836

Niemelä-Nyrhinen, J., & Seppänen, J. (2023). Photography as play: Examining constant photographing and photo sharing among young people. Visual Communication (London, England), 22(4), 581–599. 10.1177/14703572211008485

Yang, K. (2024). Your smile works: Understanding smiling face emojis in social media interactions. Visual Communication (London, England), 10.1177/14703572241268382

Zappavigna, M. (2016). Social media photography: Construing subjectivity in instagram images. Visual Communication (London, England), 15(3), 271–292. 10.1177/1470357216643220