It’s clear that our desire for multisensory experiences hasn’t faded with time. If anything, it’s evolved. It has become even more important now in this new digital world that is overflowing with content and our shrinking attention spans.

In the pre-digital age, interaction with visual design was multisensory and personal. With print, for instance, we interacted with the scent of ink, the weight and texture of the page, the way we folded, annotated, or tore out pages, and the way the paper sounded.

Before the digital era, designers were already exploring more ways to break the flatness of the page and trigger other senses besides vision. We had scratch-and-sniff perfume ads, pop-up books, textured prints, or zines you could fold, rip, and collage. These tactile and olfactory elements made print design personal and memorable.

Video by Newberry Library, 2023

Fast forward to today, and technology has offered new ways to reimagine those multisensory experiences digitally. Techniques such as haptic feedback, responsive animations, kinetic typography, sound effects, Augmented Reality (AR) features, and gamification elements are becoming integral to the designer’s toolkit. When combined thoughtfully, these layers can turn abstract ideas or flat visuals into multisensory experiences where users can explore or manipulate content.

For example, haptic feedback can enhance a digital poster, like a music festival graphic, with vibrations mimicking a beat when tapped. ASMR sound effect, like a rustle, can enrich a static magazine cover.

Responsive animations and kinetic typography, such as a graphic element morphing or text animating built with tools like Figma or Adobe After Effects, can add an engaging dynamic motion to static visuals or help explain a complex idea.

AR, powered by tools like Meta Spark, can add a 3D interaction turning a static Instagram ad, for instance, into a virtual try-on filter. An application like Artvive, can animate a gallery poster’s artwork or a billboard when scanned.

These interactive layers, such as motion, sound, clickable elements, and multimedia enhancements, can transform static visuals into dynamic, user-driven experiences. According to research, integrating interactivity into visual content can significantly improve how we engage with information (Ismaeel & Al Mulhim, 2021). The study found that interactive infographics not only boosted academic achievement, especially among reflective learners, but also enhanced cognitive processing by catering to different learning styles. This is supported by dual coding theory, which suggests that people learn more effectively when verbal and visual information is presented together through multiple sensory channels (Clark & Paivio, 1991).

By allowing users to manipulate elements, receive feedback, or navigate content at their own pace, these interactive layers can create a sense of control and immersion, which are key factors in both user engagement and accessibility.

The designer today needs to be an author creating rather than representing experiences

What does this mean for visual communication professionals? Essentially, it requires an interdisciplinary approach that combines art, psychology, technology, and strategy. Designers need more than just new technical skills like coding fundamentals, animation, AR/VR tools, and the ability to create or collaborate in motion design environments. The modern designer must be “an ‘author’ creating rather than representing experiences” (Hassenzahl, 2014).

For visual design, this means evolving far beyond aesthetics. In the digital world, the designer must become a UX storyteller, someone who considers how a design behaves, feels, responds, and unfolds over time.

They need to shape the entire user experience, anticipate needs, explore possible futures, and understand their audience’s emotional drivers and behavioral patterns.

This often requires moving away from the traditional linear design process of brief, concept, and execution, and embracing a more circular, iterative approach, one that involves continuous cycles of research, testing, and refinement to improve the user experience at every stage (Babich, 2017).

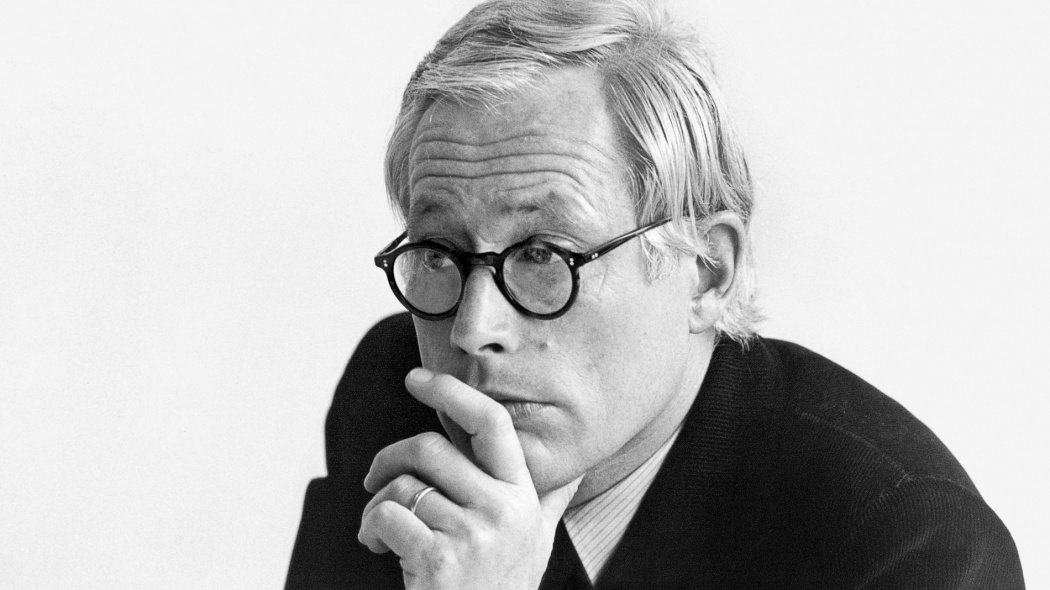

“Good design is as little design as possible. Less, but better – because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials.

Dieter Rams

Dieter Rams Photograph by Abisag Tüllmann

The primary mission for visual communicators remains the same: to create work that communicates clearly, purposefully, and memorably. Dieter Rams, a renowned designer, highlighted that good design should be invisible (Vitsœ, 2025). It should feel natural and intuitive to engage with. We must remember that, just because we have these new multidimensional tools at our disposal doesn’t mean these elements need to overwhelm our designs. As designers and communicators, we need to prioritize mindfulness and purpose, using them to embed meaning and value rather than distracting with flashy effects.

References

Babich, N. (2017, Nov 04). Moving from graphic design to UX design: The complete guide to career change. Adobe Blog, https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2017/09/04/ux-design-for-graphic-designers

Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01320076

Hassenzahl, M. (2014, Jan 1). User experience and experience design. The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd Ed., https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/user-experience-and-experience-design

Ismaeel, D., & Al Mulhim, E. (2021). The influence of interactive and static infographics on the academic achievement of reflective and impulsive students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(1), 147–162. 10.14742/ajet.6138

Vitsœ. (2025). The power of good design. https://www.vitsoe.com/us/about/good-design