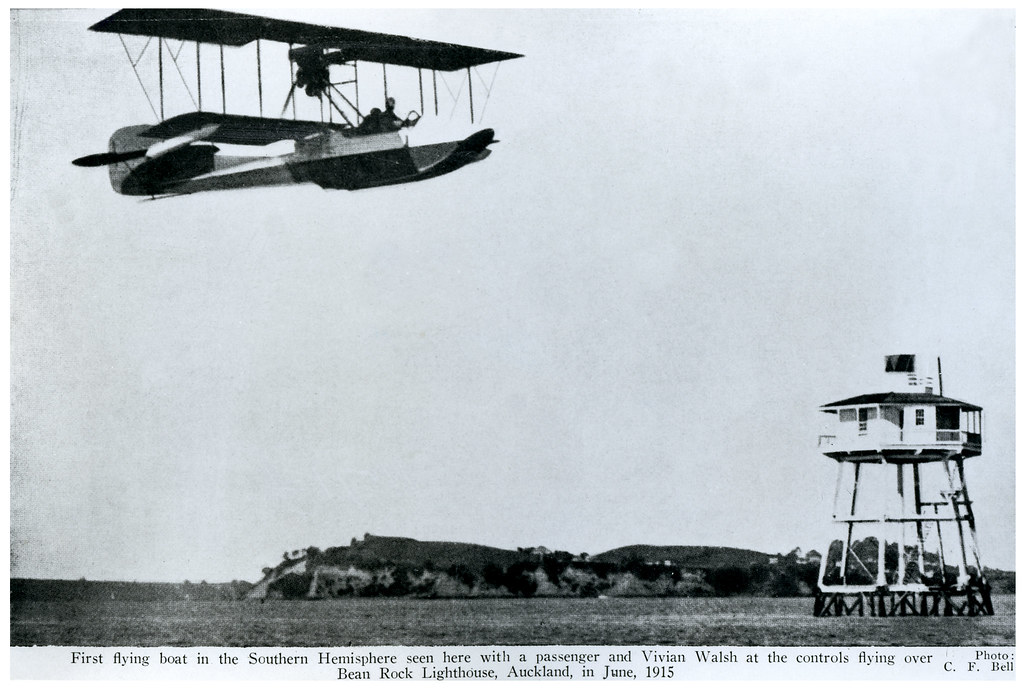

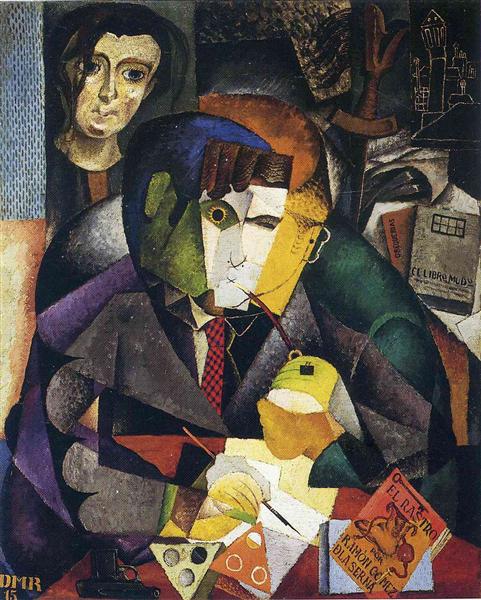

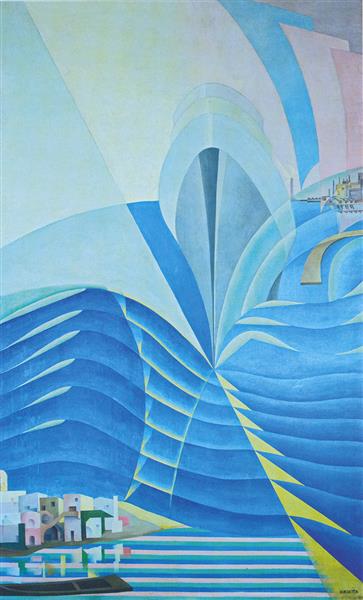

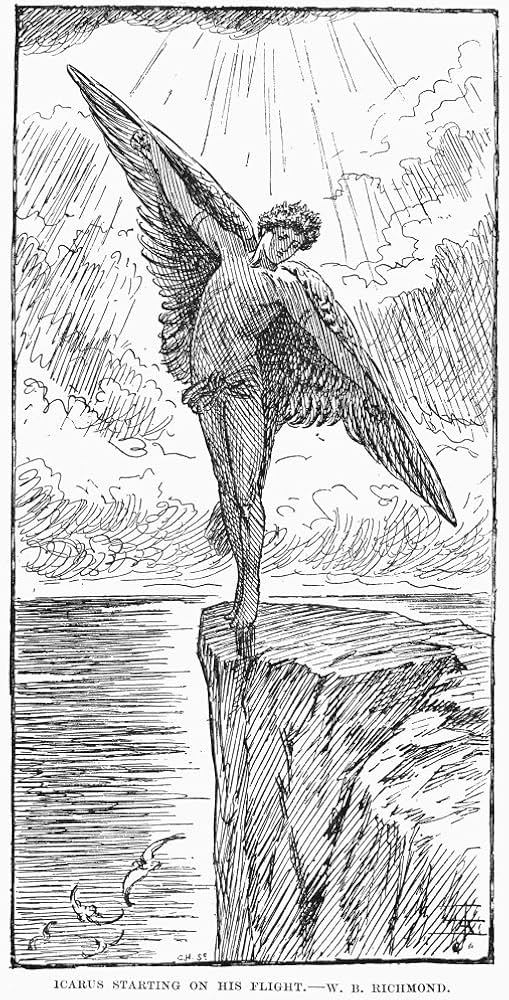

In the early 20th century, artists stood at the edge of a new world. Airplanes had taken flight, Einstein was reshaping time and space, and industry was rewriting how people lived.

Mechanical reproduction was transforming the techniques and notion of art (Benjamin, 1969).

"Together, these innovations in technology and science shocked artists, pushing them to find a new artistic language to capture the complexity of this new, multi-dimensional world.”

Avlonitou & Papadaki, 2025

Movements like Cubism, Futurism, and Constructivism challenged the very idea of what art could be. And, some art theorists believe that today, AI art is following a similar path (Avlonitou & Papadaki, 2025).

There’s a transformative impact of AI on art, challenging conventional definitions of what it means to be an artist or create art. Who (or what) is the artist, what constitutes creative intent, and can machines truly be creative?

AI art, in many ways, echoes the logic of modernism: a break from tradition, a fascination with tools, and a reimagining of the creator’s role. But this time, it’s slightly different.

The main difference between the mechanical reproductions and computer arts is that AI has greater autonomy in creation, and at times can create visuals that exceed human ability in speed and technique.

AI-powered image generation uses algorithms trained on large datasets to create original artworks. Nevertheless, it still depends on human curation, such as guiding with prompts, providing feedback, adjusting parameters, or engaging in co-creation.

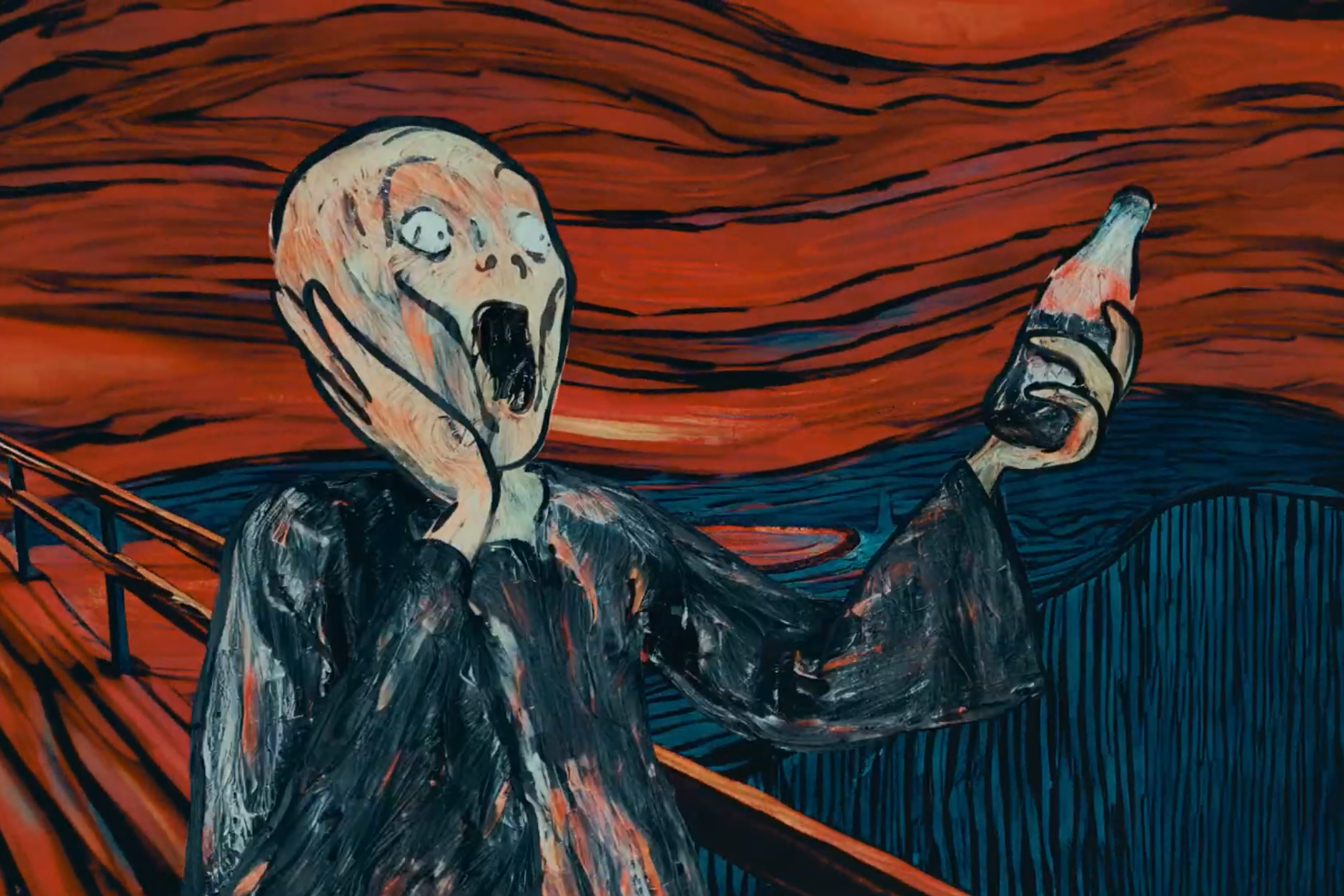

In a sense, AI art becomes less about the final visual or aesthetic outcome and more about the ideas, interactions, and philosophical questions it provokes, aligning it with conceptual art traditions (e.g., works by Marcel Duchamp, where the concept precedes the object).

Another part of what makes this moment so complex is our uneasy relationship with machine-made creativity.

Research on AI in fields like finance and visual media suggests that while machines can outperform humans on speed and scale, we still trust human judgment more when it comes to ambiguity, emotion, and nuance (Cao et al., 2024).

In visual design, this plays out in our instinctive preference for human touch, even when AI-generated work is technically flawless. We’re drawn to imperfections, backstories, and the belief that art reflects lived experience (Avlonitou & Papadaki, 2025).

In art, what we crave is evidence of intent, risk, and care. Without it, the work can feel cold, soulless, even when it’s beautiful.

“From a phenomenological perspective, human intelligence is a dynamic process rooted in logos—the interplay of thought, freedom, and meaning. Unlike machines that only classify and calculate data, human intelligence involves subjective, lived experience, where individuals interpret and create meaning through discovery, transcending mere mechanical functions, which machines are limited to.”

Avlonitou & Papadaki, 2025

So, in this context, who (or what) qualifies as the artist?

For centuries, we have associated artistic value with the originality of a creator’s vision, but generative AI challenges that idea.

AI systems are often seen as “black boxes,” with their inner workings not fully understood or disclosed (Chakravorti, 2024). Users and regulators don’t always know what training data was used or how decisions are made.

This opacity leads to ethical problems (like bias or misinformation) and legal conflicts, especially around copyright and attribution.

Many models are trained on vast datasets scraped from the internet, with millions of artworks, designs, and illustrations collected without consent or compensation (Bondari, 2025).

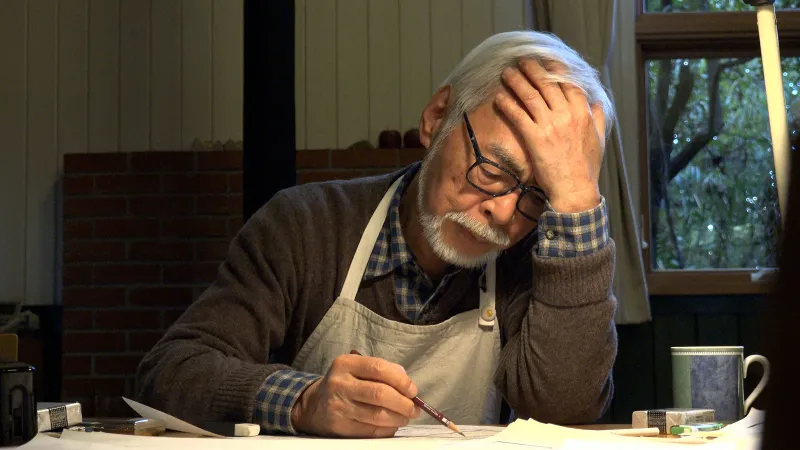

The resulting outputs can mimic specific styles, sometimes down to the smallest detail. A recent example is OpenAI’s release of a new image generator that rapidly went viral for its ability to mimic the style of Studio Ghibli.

Users flooded social media with “Ghiblified” images, while OpenAI executives actively promoted the trend. This raised serious concerns about appropriation, ownership, and creative exploitation (Alex Reisner, 2025).

Legally, current policy in the U.S. maintains that purely AI-generated work cannot be copyrighted, reinforcing the idea that authorship must come from a human mind.

But it fails to address several aspects, including visual styles, such as Studio Ghibli’s. While individual works are protected by copyright, visual styles are not (Alex Reisner, 2025).

This means that an artist’s carefully crafted style can be turned into a viral aesthetic filter, devaluing their work.

Ethically, we’re in murkier waters. If a model has learned from thousands of unlicensed human artworks, is its output truly original, or is it a polished remix of unpaid labor? Are we unintentionally infringing on the visual language artists have carefully developed over their careers, possibly devaluing their styles?

When AI imitates without context, it risks flattening visual culture. Artists, like Hayao Miyazaki, spend decades refining their styles. If platforms let anyone mimic it instantly and profit from it, they undermine the creative labor that built it in the first place. For visual communicators, this becomes a cultural issue. As designers, this forces a hard reflection not just on how we create, but on the systems we’re complicit in using.

AI synergy can democratize artistic expression and provide artists with active and innovative tools to explore new creative frontiers for the benefit of humanity. And it’s a noble vision.

However, technology can become dangerous when used without restraint or awareness. When we stop questioning, refining, or supervising what AI produces, we risk flattening our own creative judgment, and this tool can end up dictating the process, rather than supporting it.

References

Alex Reisner. (2025, May 13). ChatGPT turned into a studio ghibli machine. how is that legal? The Atlantic https://global.factiva.com/en/du/article.asp?accessionno=ATLCOM0020250514el5d00007

Avlonitou, C., & Papadaki, E. (2025). AI: An active and innovative tool for artistic creation. Arts (Basel), 14(3), 52. 10.3390/arts14030052

Benjamin, W. (1969). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Schocken Books.

Bondari, N. (2025). AI, copyright, and the law: The ongoing battle

over intellectual property rights. Gould School of Law.

Cao, S., Jiang, W., Wang, J., & Yang, B. (2024). From man vs. machine to man + machine: The art and AI of stock analyses. Journal of Financial Economics, 160, 103910–22. 10.1016/j.jfineco.2024.103910

Chakravorti, B. (2024, May 3). AI’s trust problem. Harvard Business Review,

United States Copyright Office. (2023). Copyright registration guidance: Works containing material generated by artificial intelligence. Retrieved from Research Library Prep https://www.copyright.gov/ai/ai_policy_guidance.pdf